Ale Britannia!

British Ales – Part One

I spent a lot of time travelling within the U.K. for business a few years back and came to like the British Isles very much. I still remember the first time I had an English ale. Several of us were in a country pub on a beautiful late Spring day. Our host ordered a round of ales, and I thought, “This is like Robin Hood – flagons of ale for me and my merry men!”

When the drinks came, it wasn’t love at first sip. The beer wasn’t very carbonated, and was served warmer than I was used to. As I was still un-enlightened beer-wise, I longed for a nice cold Miller Lite. But as the afternoon wore on, and we had several more pints, I was finding myself liking these strange new beers more and more.

What we were drinking was English Bitter – a beer that was destined to become my favorite style over the next few years (I had still not gone to Belgium at the time). What I learned in those years was that the United Kingdom and Ireland have a nice spectrum of great beers with many variations depending on where you are in the countries. Because they were used to listening to Americans “wining about warm beer,” my British colleagues were in awe that I not only liked their traditional beers, but had learned something about them.

Historical Perspective

British brewing has a long and storied history. Beer has been brewed in Scotland for more than 5,000 years, and in England since before the Romans arrived in 54 BC. Beer was consumed daily by all social classes during the Middle Ages, both as a food and because it was safe to drink. In those days water was largely contaminated, so everyone – even children – drank beer. In the 15th century, unhopped beer was called “ale” and the hopped version was called “beer.” The 18th and 19th centuries saw the rise of large-scale breweries and technological development.

British beers are traditionally flavorful ales of moderate strength that vary in color from pale gold to dark mahogany or jet black. They are typically malty with varying degrees of hop bitterness. Cask ales are the most traditional types and are served fresh and naturally carbonated at cellar temperature.

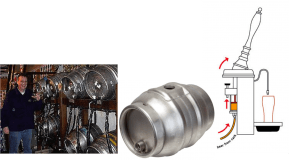

Keg or Cask?

Let’s clarify what the British mean when they talk about keg ales and cask ales. Keg ales are pretty much what we know as draft beer. The beer is pasteurized and filtered to remove the yeast. It is force-carbonated and dispensed cold with CO2 pressure. These are the beers you find in nightclubs, hotels, airports and many restaurants. Keg ales are okay, but are a far cry from traditional ales.

Cask ales, on the other hand, are true to tradition and are available in many pubs. They are unpasteurized and unfiltered, and contain live yeast. They typically come in an 11-gallon keg called a Firkin and are cask-conditioned (naturally carbonated in the keg).

They are dispensed with a hand pump without the use of CO2. The hand pump literally pulls the beer from the cask, which is usually in the cellar of the pub. These beers are served at cellar temperature (around 55° F) so they are not served warm, but cool. Once I got used to drinking beers at this temperature, I realized that it is ideal for bringing out aromas and flavors. The more you chill a beer, the more you hide its real taste. No wonder some beers want you to “wait till the mountains turn blue” before drinking them. I also appreciated the low level of carbonation, which allows you to drink more without the “bloat” associated with highly-carbonated beer.

The British Pub

The best place to find traditional cask ales is at a “pub,” or public house (as opposed to a private club). English, Scottish, Irish, and Welsh pubs are often the centers of social life for their communities. They are gathering places that often serve traditional comfort foods and are, for the most part, not that “bar-like.”

From the standpoint of beers served, there are two types of pubs. A Tied House is owned by a specific brewery and only sells that brewery’s beers, with maybe a few guest beers (like Guinness) available.

A Free House is an independently owned pub (not connected to any one brewery) that usually has a good selection of real cask-conditioned ales. Tied houses and Free houses can be identified by their signage.

Types of British Ale

In this installment, we’re going to look at several styles of British ales, including English Bitters, English Brown Ales, Scottish Ales and Welsh Ales. In British Ales – Part Two we’ll look at Porters (historic and modern), English IPAs, five different Stouts, Old Ales and Barleywines.

English Bitter

Depending on the pub, you’ll find a wide variety of beverages – including cask ales, keg ales, hard ciders, and lagers (domestic and imported), in addition to wines and spirits. Despite popular trends, cask ales are England’s true traditional (and world class) beers. Predominant is English Bitter ale. Called bitters because of their relatively high hopping rates, they come in three strengths.

Ordinary Bitter has the lowest alcohol of the bitters and is what you’ll get if you order “a pint of bitter.” Typically between 3.2% and 3.8% alcohol by volume (ABV), Ordinary Bitter is a pale amber ale with low carbonation and little head. They have medium to high bitterness, low to moderately high fruit esters, and low hop flavor with earthy, floral character. They are moderately malty with some caramel or toffee flavors. Ordinary Bitters are medium-bodied session beers that are very drinkable. They are a pub favorite because you can drink a number of them without getting intoxicated or bloated.

A Best Bitter is typically the brewery’s premium product – still a session beer – but slightly more alcoholic – in the 3.8% to 4.6% ABV range.

Though many Americans assume the biggest Bitter – Strong Bitter or English Pale Ale – is the brewery’s top product, it is not. Strong Bitters are not as popular as Ordinary or Best Bitters because the English prefer the lower gravity beers that they can drink more of without as becoming too intoxicated. Strong Bitters weigh in at between 4.6% and 6.2% ABV. Bottled or kegged versions are often referred to as English Pale Ales and are formulated differently than cask versions.

English Brown Ales

There are several styles of English Brown Ales. Among the most well-known are the popular brown ales from the north of England. Newcastle Brown and Samuel Smith’s Nut Brown Ale are popular examples, along with Wychwood Hobgoblin and Riggwelter Yorkshire Ale. These are malty beers with caramel notes, and are relatively dry. They lack the roasted character of porters. Popular on draught and in bottles, they are typically in the 4.2 to 5.4% ABV range.

There is also a London Brown Ale style that is sweeter and more caramel-focused. Manns Brown Ale is the dominant producer of this style.

English Milds

A variation on English Brown Ale is the English Mild – a low-gravity, less hoppy session ale that is brown to dark brown in color and malt-focused. Dark malts and dark sugars define this refreshing and flavorful style. Milds had fallen out of popularity for a time, but have been making a comeback in recent years. Examples include Banks’s Mild, Cain’s Dark Mild, Theakson Traditional Mild and Moorhouse Black Cat.

Scottish Ales

As I mentioned earlier, Scotland has a 5,000 year brewing history and has influenced brewing all over Europe.

Modern Scottish Ales are malt-focused with caramel notes and only enough hops to balance the malt. They can be dry and grainy, or rich, toasty and caramelly. They should not be roasty or have any smoked character. Scottish ales are typically served on draught, but there are popular bottled versions. They come in three strengths.

Scottish Light Ales – also referred to as sixty shilling. Sixty shillings was the tax on a cask in the old days and tax collectors would write this on the cask using the abbreviation 60/-. They are the least alcoholic Scottish Ales, coming in at 2.5-3.2 ABV. At this strength, they are very drinkable and the perfect session beer if you’re having several of them.

Scottish Heavy Ales (known as seventy shilling – 70/-) are essentially the same as the 60/- version but with a bit more alcohol – 3.2-3.9% ABV.

Scottish Export Ales (80/-) once again have the same flavor profile as the two lighter versions but can be anywhere from 3.9 to 6.0% ABV. Many of these beers are bottled by brands such as Belhaven, McEwan’s, and Orkney.

Finally, the strongest of Scotland’s ales is Strong Scotch Ale or “Wee Heavy.” The term “wee heavy” referred to the fact that, often packaged in a small bottle (“wee”), they are still a strong ale (“heavy”). Strong Scotch Ale (the only beer referred to as “Scotch” rather than “Scottish”) is rich, malty and caramel-sweet, but never cloying or syrupy.

Popular brands of Wee Heavy include Belhaven Wee Heavy, Gordon Highland Scotch Ale, McEwan’s Scotch Ale, Orkney Skull Splitter and Traquair House Ale.

Welsh Ales

For the most part, Welsh Ales are similar to the major British styles – Bitters, Milds, Brown Ales and IPAs. Most are malty with an earthy bitterness. Both the alcohol and the bitterness can vary.

Popular brands of Welsh Ales are Brain’s, CWRW, Celt and Fellinfoel.

What we have looked at so far are English, Scottish, and Welsh ales that are largely sessionable and thus popular in pubs. In our next segment, British Ales – Part Two we’ll look at Porters (historic and modern), English IPAs, five different styles of Stouts, Irish Ales, Old Ales and Barleywines.

In the meantime, pick up a bottle of Traquair House Ale, Fullers London Pride, or Belhaven 80/- Export, and get a good taste of the British Isles. If you’re in Denver, be sure to drop by Hogshead Brewing for some of the best English Ales anywhere. Cheers!

Leave a Reply